She stood by the climbing moonflower vine as the light faded from the sky. Her eyes were still puffy and red though it had been two hours since she’d last cried--her final sobs reaching their peak as she crossed the bridge and saw the beginning of the sunset, red, over the city.

Now she was waiting the way she always had, barefoot, outside and alone, waiting for the night to swell up around her and bring her comfort. As a teenager she had run out through the empty field where her grandfather’s cattle had once grazed; the grass was thick with clover and springy under her feet. When they were arguing she would stand in her pajamas until the cold of the dew made her legs tremble with shivers, until the moon rose up and the moonflowers opened.

She had rented this house because of the expansive plant at its southern corner. The minute she drove up the gravel drive and spied the great, fat buds “like swirls of soft ice cream”* she had known she would pay whatever the landlord asked. In the end, it had been a good price and it had been a good place for her. An empty outbuilding nearby had become her pottery studio and what had seemed to most people to be a passing whim--a few extra credits her senior year of college, was now close to becoming her vocation. She had made the jury cut and had a tent booked at the Stone Arch Bridge Art Festival later this month. She should be throwing pots now, she knew, but she didn’t move. The dark settled in around her. She waited.

They had had an argument--not anything very different from any others, but this time he was more insistent, or she more stubborn--she wasn’t sure.

“Marry me,” he had said. “Damn it, Ava, be sensible and marry me!”

She couldn’t say for sure what had made her say no--made her flat-out refuse instead of being coy and tactful. But then he had made some off-hand remark about her pottery, about how his recent promotion would provide them with more than enough and she could “keep her hobby” at least until they had children. That had made her angry, but she was old enough to sense that it had only scratched the surface of something deeper. She hadn’t expected to snap at him, but then wasn’t surprised when she did. She watched, as if from over her own shoulder as the argument turned from catty to heated. In the height of it she had closed her eyes and thought of this moment, outside, barefoot, waiting for the moonflowers to open, and it had brought her back to the meadow outside her childhood home. Her eyes had snapped open then.

“I will never marry you, Ricky!” she had said with such venom and certainty that her boyfriend-of-three-years’s jaw had dropped slightly open and hung there, gaping.

“I’ll go spend fifty bucks on a vibrator and another fifty on a bottle of wine [throw all the dame pots that I want] and get on with my life!”

The fight had only escalated after that, of course--how could it not? They had never spoken to each other that way; those words would have stung anyone.

“I was just so tired of dealing with his--” she whispered to herself in the dark, then stopped. A flutter of wings rushed by her head and she opened her eyes.

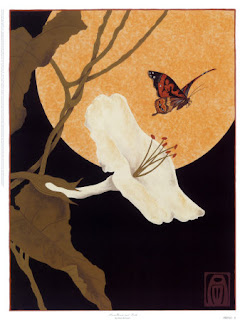

The moon had come up without her noticing. It was behind her and, thin though it was, it illuminated the enormous buds so they nearly glowed. A second sphinx moth whirred past her ear, loud as a hummingbird, and Ava saw the first flower open.

It did not unfurl or open delicately. The six-inch pearl-green petals snapped apart like the smacking of a pair of lips released from the furtive embrace of the long, hot day. A light breeze swirled the air and, “Oh, God,” she groaned with pained pleasure: the smell.

She stood there until well past midnight, unaware of the passing of time, thinking of nothing but the moonflowers, counting them as they spread themselves before her, one, two, three, sixty, eighty! She was giddy with delight, drunk on the lushness of it all--their rich perfume swathing her, the sphinx moths beating the air, brushing against her until her skin, her whole body was humming! She swayed and hummed a silent melody, she stepped out of her bitter sadness, she drank in dew through the soles of her feet.

At last when the last moth had moved on--flown to the rich and drooping lilac bush beyond the drive, she shook her wavy head, turned her face up to the million stars.

“Thank you,” she thought.

Though it was early summer and the nights were still cool, she left her bedroom windows open to the south. Alone in her double bed in her simple white nightgown, with the hoot of owls, the steady chirrup of courting frogs, and the mixture of lilac and moonflower floating in the window, Ava fell asleep.

The night was her lover and she was completely content.

-Rose Arrowsmith DeCoux

*quotation: Jenny Andrews, Garden Design, May/June 2010, “Plant Palette”

photo by Anita Munman: Moonflower & Moth

.gif)